The following is a letter I wrote to my dean, Garth Saloner, a few months ago regarding overdue reforms for Stanford's Graduate School of Business. I am choosing to publish it here as I hope it encourages others to join the cause.

The letter is long but such an audacious agenda requires a well structured essay. I admit that there may be holes in my argument but I believe the ethos is right and I hope it resonates with you, the reader.

Dear Dean Saloner,

My name is Arjun Moorthy and I'm a GSB alum, class of 2006; I was in your strategy class in 2005 as part of the GSB '06 graduating class. Your class was my favourite in school and where I received my highest marks - Honours. As an alum I am proud to see the progressive changes you've made to the GSB as dean and so I hope my appeal below will resonate with you.

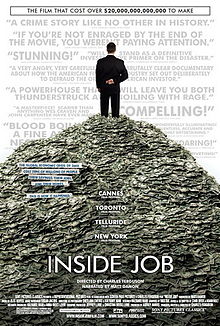

Recently I saw the documentary Inside Job on the 2008 financial crisis and the factors leading up to it. If you haven't seen it I recommend you do; if it strikes a chord with you as it did for me then you may very well consider introducing it into the curriculum.

There are several lessons I drew from the documentary that can help premier academic institutions like the GSB transform themselves so that we produce leaders who seek to prevent such systemic collapses and change organizations for the better.

A homogenous curriculum

Like all pop-documentaries there are some biases but the central theme is powerful; fundamentally, the USA has mortgaged its future by taking on incredible amounts of debt at every level - government, institutions and individuals. The problem is individuals at each of these levels were rewarded to do so in the short run – high risk but if you get the returns you are set for life.

In finance we teach the benefits of corporate debt due to the tax deductions of interest payments. Is the tax benefit of debt versus equity really supposed to guide our academic teaching? Favourable tax treatment for debt is already being seen as unnecessarily risky and maybe due for reform.

Sure we cover the risks of leverage but I suspect most students left corporate finance class after learning about Modigliani-Miller's theorem (where taxes exist) that leverage is good, especially when debt is cheap. How is it that we never challenged this idea in school?

I am particularly disappointed that the lone academic contrarian to the financial crisis who was quoted in the movie was NYU’s Nouriel Roubini. The homogenous nature of our curriculum, for example barely ever questioning ideas like efficient market theory, makes it less likely that the GSB – students or faculty – will challenge the status quo. How can we develop leaders to change anything when our curriculum does not go out of its way to present contrarian viewpoints?

(I did see a recent paper from Admati, DeMarzo et al that suggests banks should have higher levels of liquidity, that equity is cheaper than Bankers may understand, and that policies which subsidize debt are distortive. How I wish that our faculty had gone father and stated all this earlier and more publically.)

Recruitment

This brings me to the next point – the GSB has been recruiting ~30% of its graduates from the finance and PE/VC/hedge-fund industry for well over a decade yet this disproportionately represents American industry. A recent paper from the IMF and academic institutions suggests that the finance industry is bloated by a factor of two.

More damaging, the documentary states plainly what we all know: the finance industry doesn’t create any goods and ultimately doesn’t add as much value as its size should require. The rhetoric about the benefits of free capital flows is overstated as we’ve seen with countless economies swing wildly as capital flows in and out of situations with breathtaking speed. So, with such a bad reputation why are we recruiting from, and placing our best graduates into, this industry?

Of course, students will seek out the jobs that pay the best as they often graduate with sizeable loans. So, what can Stanford do to encourage taking lower paying but more important jobs to the country?

How about the GSB sharing interest payments on loans for a period of time after graduation if students chose lower paying industries? How about publically stating a shift in industries we recruit from to show the GSB’s commitment to developing leaders in industries beyond finance? (A similar but less emphatic argument could be made for consulting). How about giving greater visibility to non-finance sectors, perhaps through the establishment of a Center for Policy studies or having our career placement services actively solicit jobs in the public sector and NGOs? Top positions in these sectors pay competitive salaries so this won’t be a massive sacrifice for our graduates.

Greed

Of course the pursuit of high salaries is core to capitalism and is healthy to some degree but there’s no getting away from the fact that most disasters in business are driven by greed.

A recent Princeton study shows that happiness levels off at $75,000/year salary. While minor points in the study can be argued (adjust for cost of living in regions etc.) the conclusion is that at a relatively modest salary level happiness levels off. So, what is driving graduates to take jobs that pay more? Part of the reason is a chance to work with the brightest minds (and hence we come back to recruitment and placement into select industries) but part of it is just greed and a never ending quest for personal wealth.

I don’t know how a school can teach the dangers of greed but if we aim to develop leaders I feel this is an area the GSB must address. History usually shows that most leaders and innovators changed the world more because of driving passion than by a desire to be obscenely wealthy. And there is certainly precedence in academicians like Adam Smith affirming that the study of economics requires the study of morality and politics.

Certainly the service learning trips the GSB has instituted go some ways to showing students what life is like for the 50% of the world that lives on less than $2/day. Can we make such trips longer than two weeks and a mandatory part of the curriculum? Should our curriculum require courses in philosophy, political science and history? Should MBA students have a professional certification exam and perhaps an oath, similar to the Hippocratic Oath, that requires them to act in the interest of society? Will such a certification and oath keep US educated MBAs sought after and admired for decades to come, particularly as the world economy tilts in favour of non-US countries?

Aside: academic integrity

The documentary's most startling revelation is the complicity of academicians in promoting deregulation, particularly prohibiting the regulation of derivatives and the supposed benefits of "spreading risk" through opaque instruments. Further atrocious decision by these academics include supporting the merging of deposit holding banks and investment banks in the name of aiding capital flows but really spurring speculative investing.

Columbia Business School’s Dean Glenn Hubbard comes off looking at best stupid and at worst knowing misleading with his advice to the US government. Harvard looks almost as bad when John Campbell, the chairman of Harvard’s Economics Department, says he sees no need for professors to divulge their funding sources when doing independent consulting.

This it to say nothing of notable graduates and faculty of leading business schools - Harvard’s Larry Summers, Harvard’s former Goldman CEO Henry Paulson, London School of Economics’ Robert Rubin (Harvard honorary degree), NYU’s Alan Greenspan and even the GSB’s Ben Bernanke – who all led the government astray in encouraging policies that benefited Wall Street and risked the taxpayer’s base.

Though Stanford is not explicitly mentioned in the documentary I suspect that our professors and graduates would likely have followed a similar path if they had been in the same position as the aforementioned people. Should this be a warning sign for how Stanford sets guidelines for its faculty and its graduates? Columbia and Harvard have since changed their guidelines on disclosure but this seems a tiny step given the magnitude of the disaster their policies influenced.

Closing

Our motto is to Change lives, Change organizations, Change the world. Honestly, I felt this was trite while attending the GSB but 5 years on I actually believe each graduate can do this.

The US may very well be looking at decades of zero growth ahead, akin to Japan's lost decades. If we want GSB graduates to change the world here's our chance.

We don't need more recruits from, or graduates going into, finance related fields. We need to diversity our student base and place graduates in fields that shape the country not because of the wealth of individuals but rather the responsibility they hold in their positions.

We need to reform our curriculum to show a broader spectrum of ideas and push to question conventional wisdom at other supposed leading schools and even public institutions. Taking a page from Clayton Christensen, I would look to see how we can disrupt the GSB each and every year.

We need to integrate the teaching of morality as part of building leaders. Whether this comes from a professional certification or oath, graduates need to understand (and perhaps be reminded of often) their responsibilities beyond themselves and their role in society at large.

The GSB has changed the trajectory of my career but even I have not yet lived up to our motto. I am slowly moving my career in the above direction but one step I did take after seeing the movie: I publically liquidated all my direct stockholdings in the financial sector and will never again be a shareholder of such corporations until they reform moral hazard, compensation structures and board constitutions.

A suitable next step may be to set up a committee consisting of faculty, alumni and students to probe these issues further and recommend what changes Stanford GSB should undertake to build leaders that really change the world. If you agree I am happy to volunteer to be part of such a group.

Thank you,

Arjun Moorthy (MBA ’06)

Epilogue: Dean Saloner replied and agreed that change was needed and underway. Coincidentally, just after I sent this letter the GSB unveiled its new Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economies. And select professors continue to push out papers on what really caused the financial meltdown. But these actions do not address all the concerns raised above and hence I felt it was useful to post the letter in a public forum.